Public Spaces: A platform to connect during COVID-19 and build equitable cities beyond

On March 24, 2021, Knight Foundation released “Adaptive Public Space: Places for People in the Pandemic and Beyond”, a Knight-commissioned report examining seven public spaces across the U.S. to identify what made them successful and to offer recommendations for developing equitable and inclusive spaces beyond the pandemic. Click here to see the report. Knight’s Lilly Weinberg and Evette Alexander share more below.

A year has passed since COVID-19 transformed our lives, paradoxically accelerating our adoption of virtual spheres while increasing our reliance on outdoor public spaces that have the power to connect and attach us to community.

We’ve witnessed record usage of these public spaces, underlining how important they are to the resilience of communities. COVID-19 provided an unexpected moment of permission — it allowed our cities to innovate and think far beyond the confines of traditional public spaces. And it has been a moment to acknowledge the racial inequities that persist in our cities. Which leaves us with the question: how can we leverage this moment in time, when billions of stimulus and other federal dollars are being released for infrastructure projects, to build more inclusive, equitable public spaces moving forward?

At Knight Foundation, we value the power of public spaces to connect and attach community members. We’ve invested $54 million towards public spaces that are accessible and welcoming to all walks of life, and we see them as central to building informed and engaged communities. That’s why we commissioned Gehl, a global leader in people-centric urban design, to conduct an impact-assessment study of seven flagship public spaces sites operating before and during the pandemic.

The report released today, “Adaptive Public Space: Places for People in the Pandemic and Beyond,” holds insights for urbanists, foundations, community advocates, public officials and private-sector leaders interested in how responsive public spaces can thrive and be a vehicle for communities to address equitable development.

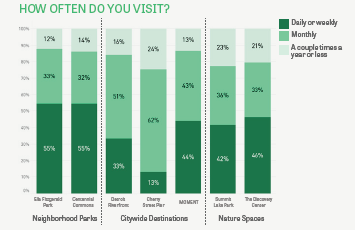

The study leverages a variety of pre-pandemic and mid-pandemic data for seven outdoor public spaces — prime examples of neighborhood parks, city-wide destinations and nature oases — operating across four cities: Akron (Summit Lake Park), Detroit (Ella Fitzgerald Park, Detroit Riverfront), Philadelphia (Centennial Commons, Cherry Street Pier and The Discovery Center) and San Jose (MOMENT). Gehl conducted interviews, surveys and focus groups with residents; analyzed data collected online from visitors; and compiled existing and new observational data on each space.

The findings are illuminating, and point to a more impactful path for inclusive public space investment amid the COVID-19 recovery and beyond:

- Spaces that reflected resident needs, historic character and the arts had more regular visits from residents.

- Community participation and responsive engagement methods allowed space organizers to build trust and enthusiasm with residents of color.

- Prioritizing and embedding resident engagement throughout the entire lifecycle led to community ripple effects like wider local capacity-building and community development beyond the project site.

- Flexible community-led design, inclusive processes and capacity-building helped sites develop sustainable operating models and adapt to changing conditions — including the pandemic.

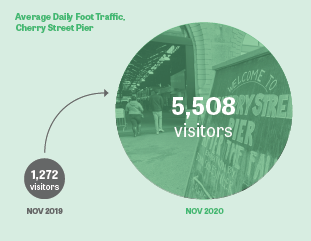

Findings remind us that the fundamentals matter: public spaces work best when they intentionally cater to the needs, history and issues relevant to residents. And these same community engagement principles enabled them to adapt and thrive amid COVID-19. For example, daily visitorship was up over 300% year over year at Philadelphia’s Cherry Street Pier, which provided spaces for local artists, a market for displaced small businesses and a garden restaurant adapted for pandemic conditions. At the Detroit Riverfront, residents self-organized regular yoga and flamenco classes, helping the space achieve last year’s visitor numbers in half the time.

As cities emerge from the pandemic, these lessons illustrate the power of public spaces as a platform for community development and addressing deeply rooted, systemic inequalities in our communities that COVID-19 only exacerbated. Open public spaces do not always translate into welcoming, safe or accessible spaces for communities of color, and the racial justice movement that played out in many public spaces in 2020 served to highlight these realities. Concerns raised by the Black community about policing is an issue some sites are addressing head on in order for residents — particularly Black men — to feel safe and welcome in these spaces long term.

To address equity, organizers must consider how they might share and shift decision-making power throughout the entire lifecycle of a public space, from initial design through governance, to include residents as partners. Detroit’s Ella Fitzgerald Park used pilots like a pop-up bike repair shop to reach residents typically under-represented at community meetings. Now, Black residents report that the park is special to them, and over half of the neighborhood visits weekly. The benefits of such engagement methods are clear: increased resident usage that helps deepen attachment to their cities.

For city leaders, policymakers, practitioners and funders like ourselves, these findings are a call to action to ensure that barriers to public spaces are reduced for all communities and that all feel a sense of belonging and welcome at every park, pier and civic common. For that to happen, planners and designers need to focus on resident needs for both the design and programming of these spaces.

COVID-19 has sparked a unique opportunity for innovation as communities rapidly repurposed public spaces during the pandemic. We can observe and learn from the ways residents have been self-organizing activities in these spaces during the pandemic — from socially distant hula hooping and flamenco, to neighborhood streets being used as civic commons — and from new ways technology can be leveraged to improve decision-making and engagement.

With the availability of more federal dollars for infrastructure, the leadership of our communities — advocates, city administrators, public and private sector leaders — have a historic opportunity to put the funding to good use by supporting equitable, accessible and engaging spaces that support more resilient cities. Now is the time to invest in community-led and empowering public spaces that can adapt to changing needs of residents during these uncertain times and beyond.

Lilly Weinberg is senior director for community and national initiatives and Evette Alexander is a director of learning and impact at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Image (top) of Detroit Riverfront Valade Park by Detroit Riverfront Conservancy.

Recent Content

-

Communities / Article

-

Communities / Article

-

Communities / Article